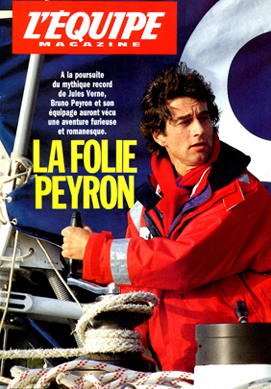

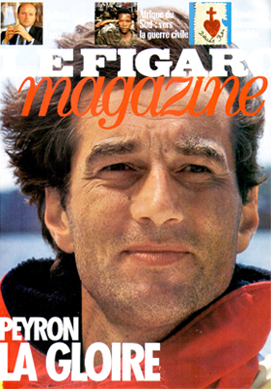

Bruno Peyron / Commodore Explorer

On board the Commodore Explorer, the biggest catamaran of its generation, Bruno Peyron opened the way with a supreme circumnavigation in under 80 days. No one had ever attempted the adventure, even less so on such a vessel. Peyron and his four-man crew took up Phileas Fogg’s challenge(1)(1) Collector pin !

. In their way stood impressive rivals and the extreme conditions of the globe’s fiercest seas.

Ushant, on Saturday 30 January 1993. At 14 hours, two minutes and 27 seconds, under full main and solent jib, Commodore Explorer crossed the starting line… With a seven-hour delay. Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston, on board their catamaran ENZA New Zealand, had left in the early morning, also on the hunt for the Jules Verne Trophy. This postponed departure would offer Bruno Peyron and his crew a magnificent opportunity to exceed themselves. They needed to catch up with the Kiwis. “We’ve attacked our journey like a gigantic regatta rather than a long-haul rally,” declared Bruno by radio on 2 February.

The two competitors were also on the heels of Olivier de Kersauzon, who had embarked on his circumnavigation five days earlier, on board the trimaran Charal. “Kersau” wasn’t one to bend to his chums’ games. He set his own rules. He was running outside the Trophy. But “the Admiral” was determined to go under 80 days and to snatch up the record.

30 January 1993. Peter Blake, Robin Knox-Johnston and French skipper Bruno Peyron look at the last weather forecasts some hours before starting from Brest. Sir Peter Blake Trust of NZ © Christian Février

30 January 1993. Peter Blake, Robin Knox-Johnston and French skipper Bruno Peyron look at the last weather forecasts some hours before starting from Brest. Sir Peter Blake Trust of NZ © Christian Février

Just as determined, Bruno Peyron showed great prudence nonetheless. How would a gigantic catamaran behave in the ocean and in the high-latitude weather? Commodore Explorer was the “world-toured” ex-Jet Services(2)(2) In 1993, at the time when Bruno Peyron purchased it, Jet Services V was the fastest catamaran in the world, with an Atlantic crossing record of 6 days and 13 hours., measuring 26 meters. A “wind-making machine,” tailor-made for racing but very difficult to brake and… more stable upside down than right-way up. The architect of the “blue rocket” designed the floats as two survival packs where the crew could spend a month if ever the boat capsized.

For Bruno Peyron, the Jules Verne Trophy was a research field for constructing a “catamaran for the year 2000,” 40 meters long in his dreams. He admitted that his only goal was to return to Ushant after scoring the best time and beating the established record – the very accessible one set by Titouan Lamazou who tied up his world tour, singlehandedly on a monohull, in 109 days. And also to bring the boat – and above all his men! – back home!

Commodore Explorer’s dream team : Marc Vallin, Jacques Vincent, Bruno Peyron, Cam Lewis, Thomas Coville (who was not onboard Commodore Explorer during this attempt for the Jules Verne Trophy), Olivier Despaigne. © Photo Jacques Vapillon.

Commodore Explorer’s dream team : Marc Vallin, Jacques Vincent, Bruno Peyron, Cam Lewis, Thomas Coville (who was not onboard Commodore Explorer during this attempt for the Jules Verne Trophy), Olivier Despaigne. © Photo Jacques Vapillon.

Record to the Equator

“There aren’t five too many of us to do the daily chores,” confided Bruno Peyron, just four days after casting off. “We tend to run Commodore Explorer in the way that we would for a Grand Prix, that ordinarily ‘consumes’ about ten big lads.” Meanwhile, ENZA carried a crew of seven, so while adding to the weight, the men were less worn by effort. In the dual between the two catamarans, Commodore Explorer quickly took the lead on the Atlantic.

While Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston hugged the African coast, Bruno Peyron traced a far more westward curve, in search of east wind. The blue catamaran soon scampered southwards, with a beam wind, at 20 knots, its favorite speed. The Commodore boys, now in the lead, crossed the Doldrums(3)(3)The Intertropical Convergence Zone, or “the Doldrums,” is a cloudy zone near the Equator, characterized by an extremely capricious wind system, varying from dead calm to sudden gusts at over 30 knots (55 km/h).. without much difficulty. On 9 February, Peyron’s Magic Team crossed the Equator, swiping its first record(4)(4)English Channel – Equator in 8 days, 19 hours, 25 minutes and 45 seconds..

© Photo Christian Février

© Photo Christian Février

Peyron in hell

Since leaving Brest, the vessel’s chart reader had been on the blink. The SSB radio link was not always reliable. Bruno Peyron had to trust in his intuition and could only rely on written forecasts, received daily by telex. As the crew approached the Great South, Météo France announced storm winds of up to 50 knots (92 km/h) – only to be expected in the Roaring Forties that Commodore Explorer was sailing through on 17 February. The thing was, an ice alert was also issued early on by Kersauson, who at that point was only 450 miles (830 km) ahead. A drifting growler had just ripped into one of Charal’s floats and the boat was forced to abandon the competition. Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Jonhston continued eastwards on their way, paying heed not to venture beyond the 38th parallel. Despite the prospect of a minefield, Peyron, still in the lead, was trying to gain yet more time and headed a few degrees south… Too far south.

“It’s an initiation to Hell. Brutal. Violent. Powerful. Outrageous! There are no specific adjectives for describing what’s happening here at the moment,” wrote Bruno Peyron about his 42° south experience. “We’ve changed scales and changed planets. Commodore Explorer is without a doubt the biggest catamaran, but here it just doesn’t exist… We almost capsized…” Colossal waves opened up gulfs under the Commodore Explorer, speeding along at 30 knots in the tempest. Peyron’s men struggled for forty hours in their attempt to keep the monster under control. These experienced sailors had never seen such a violent sea. The barepoled boat pulled through without major damage. A miracle. But for the crew, the ordeal was grueling, and they’d take a few weeks to get over it.

Alone in the running

As the boat rounded the Cape of Good Hope on 22 February, Bruno Peyron allowed himself to believe in the Trophy once again. After the shocking introduction to the Forties, and despite the need of a few repairs along the way, Commodore Explorer had swallowed up the miles – 466 miles (863 km) on 25 February – stealing those that again had been lost in ENZA’s favor. The regatta of the giants continued unabated.

But on 27 February, the New Zealander catamaran collided with an unidentified floating object. The blow was fatal: Blake and Robin in turn abandoned the race and headed for South Africa. Commodore Explorer nearly joined them. The day before, a particularly violent wave abeam struck the starboard side. Repairs lasted all night long before the leak was finally plugged up.

After 33 days, 8 hours and 46 minutes at sea, the last catamaran in the running crossed, at 50° south, the longitude of Cape Leeuwin, off Australia. A never-seen record that Bruno Peyron’s HQ rates as following the trail of the great nineteenth-century clippers.

The weather was milder as they entered the Pacific. At an average speed of 16 knots, Commodore Explorer approached the continent of Antarctica by a few more degrees, drawing near to 56° south, the longitude of Cape Horn. The next ordeal.

The “Horn wrecks”

“We’re still upright,” wrote Bruno Peyron in his logbook on 22 March, “and yet with 45 knots of south wind against us as we approach Cape Horn, they say this is only the case 10 % of the time…” Two lows had turned up in the zone, and the slot of passable weather was narrow and inconstant. Caught up by gusts at 70 knots (130 km/h), Commodore Explorer, threatened with explosion in full flight, sailed ahull(5)(5)Crossing wind and waves with sails furled.. “Inside, we’re getting everything ready for the possibility of capsizing,” described the skipper. “We’re drifting at 4 knots towards the coast. We’re less than 100 miles (185 km) from the coast. Not good.”

This caused more of a fright than real damage… Once again, the boat and the men clung on. On 25 March, thanks to a “lull” – winds at 45 knots (83 km/h) – and after 53 days of sailing, they finally went round Cape Horn.

The challenge also provided an opportunity to test new embedded technologies. On board and on land, cheers met the new prowess: a photo of the “Horn wrecks” was transmitted to Paris by satellite(6)(6) ! To find out everything on the Commodore Explorer, French fans could also consult their Minitel (a pre-Web online service accessible through phone lines)…

! To find out everything on the Commodore Explorer, French fans could also consult their Minitel (a pre-Web online service accessible through phone lines)…

Farewell, Trophy?

Once Cape Horn was behind them, there remained 9,000 miles (16,668 km) before reaching Ushant, in other words the last third of the itinerary. If Commodore Explorer was to pass the finishing line in time, before 21 April, it would have to keep up an average of 14.5 knots. But the catamaran, designed for speeding downwind, resisted high performance when going upwind. Yet the return to the Atlantic began with around ten days of sailing close-hauled upwind, up to the northern point of Brazil. After Brazil, bypassing of the Azores High by the west would lengthen the course. On 10 April, Commodore Explorer, surging once again at 17 knots, collided against two whales. On 16 April, a wooden ball crushed the stem. The boat took blow after blow, the crew tried to keep their spirits up when the average daily speed fell to 4 knots. Three days before the arrival, the skipper still doubted his capacity to win Phileas Fogg’s bet. As misfortunes arose and needed to be kept at a distance, Peyron repeated over and over: “It’s not a priority.”

Hope reemerged on 17 April: Commodore Explorer made one last sprint. At an average of 21 knots, it gulped up 507 miles (938 km) in a single day. Nothing could stop in any longer, not even the final storm that met the boys as they approached Brittany.

On 20 April 1993, the blue catamaran went over the finishing line of the Jules Verne Trophy, under the monumental Créach’, the western lighthouse of Ushant. Bruno Peyron’s Magic Team pulverized the circumnavigation speed record… and won the wager in 79 days, 6 hours, 15 minutes and 56 seconds(7)(7)

.

.

Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston had already decided to do better. Olivier de Kersauzon was also preparing his revenge…

Commodore Explorer over the finishing line of the Jules Verne Trophy, not far from Ushant © Photo Christian Février

Commodore Explorer over the finishing line of the Jules Verne Trophy, not far from Ushant © Photo Christian Février

6h | 15min | 56s

1993

1993-02-18

1993-02-18

49° 29’S

49° 29’S

10

1760

30

LOADING...

1993-02-04

26° 46’N

18° 05’W

190

1442

17

LOADING...

1993-02-26

41° 15 S

55° 05 E

LOADING...

1993-04-13

12h53

20°41 N

41° 51 W

330

LOADING...