So what if we were to look at the Jules Verne Trophy from the perspective of the summit it represents in the world of offshore racing? On its journey around the planet with the clock as its implacable adversary, this sailing record undoubtedly and figuratively ranks as one of the toughest mountains to climb. The challenge taken up by the men of Gitana Team is massive, namely a circumnavigation of the blue planet at a cracking pace to secure a new reference time under 40 days and 23 hours. In the high seas, just like in the high mountains, the challenges which push the envelope of human performance are both particularly dependent on the weather. Their success is inextricably linked to this component and with it the goodwill of Nature, which always has the final say. Little wonder then that when these two sports take the form of a feat on the crest of the waves or on the roof of the world, they have the distinctive feature of giving rise to remote weather routing with forecasts tailored for extreme environments. It is an art, a science in its own right where expertise takes precedence, some of the secrets to which are shared with us by Marcel van Triest, who is supporting the Maxi Edmond de Rothschild in her round the world navigation, and by Yan Giezendanner, a forecaster who in recent days has completed the routing for an historic winter ascent of K2…

Sorcerer of the seas Vs guru of the summits

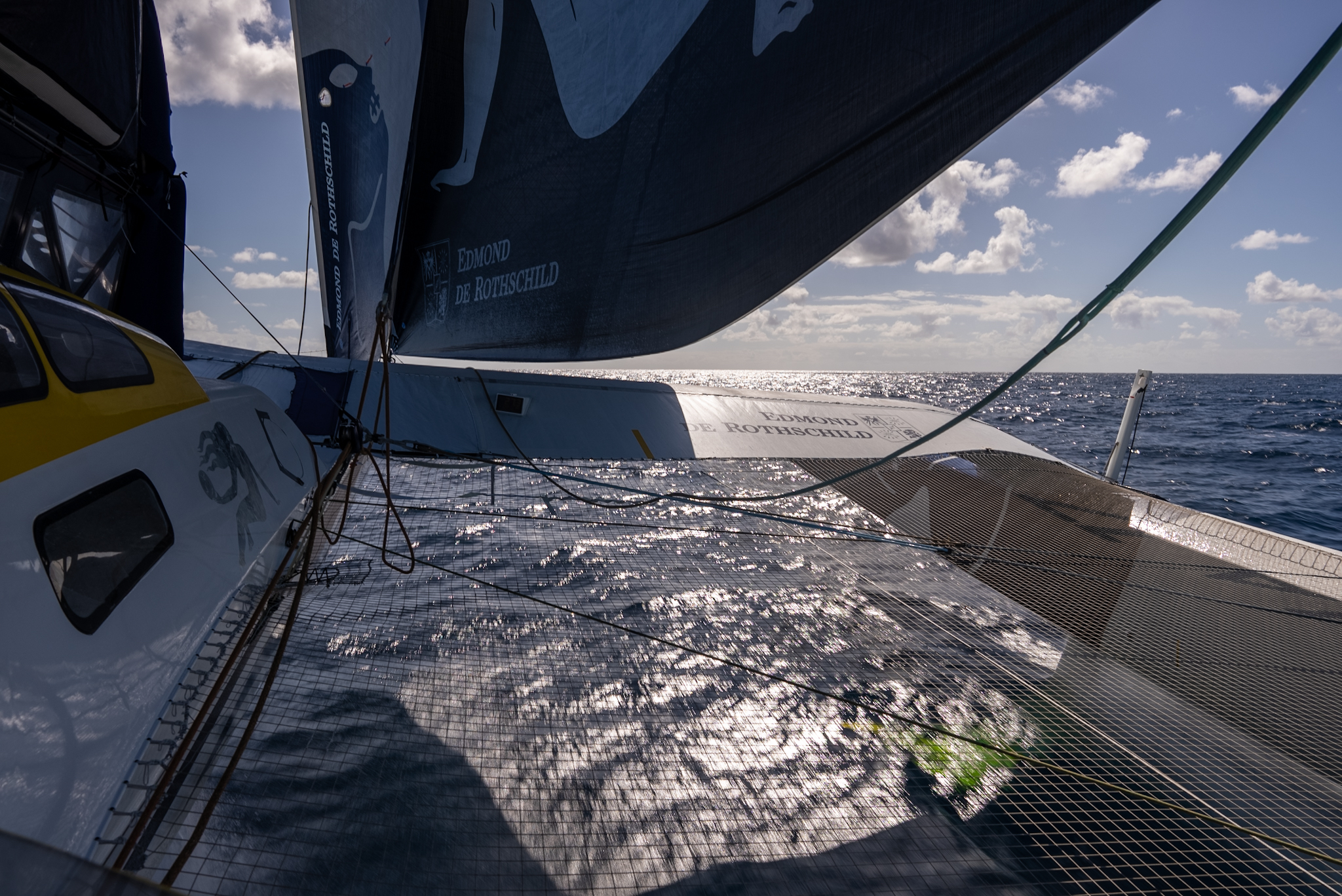

In its quest for the Jules Verne Trophy, it is through a close and constant relationship with Marcel Van Triest that the crew of the Maxi Edmond de Rothschild is today carving out a wake towards the Southern Ocean, which it should reach in a few days’ time. This polyglot Dutchman is the 7th man of the five-arrow team. He is a rather special member of the crew, who has made round the world campaigns and navigation in the hostile latitudes of the Deep South his great speciality and trademark. From his Mediterranean HQ, he is vicariously participating in this record attempt being undertaken by the six members of the crew aboard the latest Gitana. With this goal, it is his mission to locate the magical way through, “this optimal route, which may not necessarily be the shortest, but is the quickest,” the route which gives the 32-metre giant every opportunity of a successful oceanic sprint. At this level, every hour spent navigating this course of around 22,000 miles (40,744 km) counts. This provides some insight into what is required in a gamble of this kind and the importance assumed by reading oceanic weather, which remains the prerogative of a precious few who are experts in the art of deciphering charts and models of all the world’s seas which are effectively one large ocean.

“The router is a bit like a reclusive caveman, completely shut away and living his life connected up to his computers, which remain tuned into the boat 24/7, 7 days a week. As such, whilst I’m routing, I never sleep for more than an hour in a row. I have a lot of alarms around me, which I adjust according to expected performance in the conditions it is encountering. If the crew want to call me up, they can also slow the boat down… That too works very well!” explains the man, who is today living and working at the tempo of the Maxi Edmond de Rothschild, whose progress he tracks, attuned to the conditions it’s encountering and the progress displayed by the data he receives continuously in elapsed time. “Twice a day, morning and evening, I send a summary to the boat, an outline diagram for an overall approach, which I put together using thirty or so models for the next eight to ten days. Beyond the safety aspect, one of the challenges is to avoid ending up in a cul de sac, in a situation from which there is no way out. I have to be one step ahead or rather an ocean ahead at all times,” explains the Jules Verne Trophy specialist, who has been the router for the last two crews to set a reference time on the planetary course, that of Loïck Peyron in 2012 and that of Francis Joyon, in January 2017.

Conquering an historic summit in mountaineering

At high altitude, Yan Giezendanner, a 66-year forecaster who boasts 43 years of good and faithful service at Météo France, the national meteorological service, has always devoted his talents to the mountain universe. From his base camp in Chamonix, he too works with his eyes riveted to his computer screens, which he never turns off. However, his mind extends to the highest summits on the planet, which he has scaled through routing, from the Himalayan mountain range, to Mount McKinley (Denali) in Alaska, via the Antarctic and Patagonia… The man known by his experienced mountaineer peers as the ‘third man of the roped party’, boasts a list of achievements that is as long as a windless day in the doldrums. With around twenty or so Everest ascents to his credit and a string of summits of which he knows all the routes and features, today Yan Giezendanner is the only Frenchman to have successfully completed the ‘fourteen 8,000m peaks’. This outstanding meteorologist has enabled the top mountaineers to achieve this feat. “I know these 8,000m peaks. I know where you have to go, the climatic constants and why they take place… I make the distinction between Everest, Makalu, McKinley, Fitz Roy and of course K2, the furthest north of the 8,000m peaks”, explains this expert observer of what the weather is doing in spheres perched very high above sea level. This is evidenced by the prestigious route he has just pinpointed for a Nepalese expedition to conquer the second highest peak in the world (8,611 metres), the formidable K2, which had never been summited in winter before, and could not have been timed better. Hot off the presses, it is the perfect illustration of a whole list of meteorological achievements, which are fleshed out with every passing year in the high mountains.

In the Karakoram range in Pakistan, this particularly hostile mountain resisted all winter attempts at the summit for over 15 years. To reach it, you have to edge your way along a colossal glacier and skirt the Chinese border. Here, between the two countries, the mountain rises up, pyramidal, vertiginous, in the icy sky, where the temperatures hover around -50°, sometimes dropping to -60° on the sections around the summit. “It’s an extraordinary challenge that these Nepalese have just pulled off. It’s a major world first on one of the last great challenges to be taken up in the Himalayas. This ascent is hugely risky due to the cold, acute mountain sickness, snowfall, avalanches and route errors…” bears out the man who, once again, has just demonstrated the pertinence of his forecasts, at the end of an ascent officially completed on Saturday 16 January. “For several days, I’d been watching an ascent window for these mountaineers, who had acclimatised well over recent weeks. I saw the fine weather arriving and was able to give them the start signal by indicating the right moment to set off on this final route to make the dangerous summit. It was the last challenge left in the Himalayas and, inevitably, succeeding is a great pleasure.”

At the discretion of the jet stream

“My work is very similar to that which can be done by a router for a maritime expedition, the only difference being that in sailing the weather watch is constant, the monitoring permanent and without interruption, which makes things a little more complicated”, adds the meteorologist for the highest peaks, though he too has to avoid the pitfalls that punctuate the terrain in this hostile universe: serac barriers or crevasses, the negotiation of which can massively delay climbers, both on the ascent and the descent. “I began routing for mountaineers in the eighties, at a time when they were linking together major routes like the Matterhorn and the Grandes Jorasses… In 1995, with the arrival of the Internet, I was able to send information to the mountaineers taking on climbs in the Himalayas, at which point my remote routing work really took off”, explains the man who now spends his time watching the movements and developments of the jet stream. “In the Himalayas, which are located at a latitude of 35° north, I’m constantly battling with this powerful current of air, which ranges between 50 to 250 km/hr (from 27 to 135 knots) at high altitude. As it does a lap of the Earth, I follow this undulating jet and its twists and turns. Where there is a break in these turns, there is no more breeze and that’s where a favourable weather window presented itself to reach the 8,600-metre K2”, says this enthusiast of the high mountains, who is delighted at the advances made in equipment, oxygen supply and the precision of weather forecasts, which are synonymous with increased safety in the practice of this high-risk sport.

In his exchanges with mountaineers whose rope parties he tracks, Yan Giezendanner sends daily weather forecasts via email and satellite phone indicating what the weather will be like and the various episodes expected (snowfall, foggy patches…). Unlike Marcel van Triest though, who favours written messaging, which can be reread, thus preventing the loss of information in the ambient din of a giant driving flat out, the high mountain router makes phone calls to the expedition leaders who are making headway at altitudes where the satellite connections are very good. “I always speak directly to the team. That enables us to be completely in agreement about the strategy to follow throughout the acclimatisation period and during the final ascent to the summit. When I talk to mountaineers directly, I also get an understanding of what shape they’re in”, reasons the router, who likes to concoct tailored forecasts for expeditions heading up to the lofty heights where planes fly.

In search of a fast track for flight in the open ocean

On the oceans of the globe and when designing a trajectory for the Maxi Edmond de Rothschild, Marcel Van Triest uses the utmost vigilance at all times to monitor and observe the other systems, which operate with their own mechanisms. After the intertropical convergence zone, which more than lived up to its reputation – unpredictable and very difficult to negotiate – Gitana Team’s router is focusing his attention on the train of low-pressure systems in the southern hemisphere. It is at the leading edge of one of these low-pressure systems that he’d like to position the Maxi Edmond de Rothschild, which has latched back on to some more favourable winds to extend her lead as she gulps down the latitudes on her way towards the famous route around the three capes surrounding the Antarctic continent. In this environment, which can serve up extreme conditions round the clock to the men and their boat, he seeks to locate the fast track, which will enable the trimaran geared for offshore flight to avoid a battering from the nasty Deep South and dodge as many zones of turbulence with bad swell as possible so as not to impinge on their ability to maintain high speeds. “Ideally, you want to find the right balance between a route that’s not too long and hence quite far south, and a trajectory that avoids the heavy seas you encounter in the furious fifties. The dream situation, which enables thousands of miles to be covered at the best constant speed, may well exist at the 35th parallel. However, ideal configurations are few and far between and it is by enabling the team to get close to this that the weather router plays a crucial role in this record hunt”, he adds.

Approaching the great liquid desert that forms such an epic passage on this planetary course under sail, Marcel van Triest is stepping up his vigilance in his observation of the ice, a topic he excels in. “In the past ten years, we’ve seen great progress in the ability to obtain images from space. Via the CLS (Satellite Data Collection) models, we have a far greater ability to visualise the presence of icebergs. This year, the austral summer has proven to be fairly ‘calm’. The situation is pretty clear, even though there is quite a large concentration appearing in the South Atlantic, to the north of South Georgia. There doesn’t seem to be any ice in the Pacific, as there was during Banque Populaire V’s record attempt, where there was an enormous iceberg breaking up in the middle of the track, adds Gitana Team’s router, whose work today is designed to break a record he already holds. “Over the past ten years, the role of the weather has intensified a great deal. It is central to the success of an attempt”, he asserts, well-placed to gauge the difficulty of a mission to circumnavigate the blue planet via its express way, which is akin to the north face of a mountain.

“We work in the same atmosphere, but in the sailing universe it’s doubtless more complicated, with numerous wind parameters to factor in, like the strength or direction, as well as the sea state, which is crucially important. However, in an extreme environment, be that on land or at sea, weather routing is a first-rate strategic support in the quest for performance. On the oceans, as is the case on the highest mountains, records are set to be broken”, echoes Yan Giezendanner, which is inevitably what we want and have every reason to believe…