Still awaiting a favourable weather window, the Sails of Change team has decided to extend its standby period until the end of January: a very welcome extra fortnight due to the currently unfavourable situation in the Atlantic.

Throughout the autumn, there hasn’t been a single opportunity to try to beat the round the world record under sail set in 2017 in a time of 40 days 23 hours and 30 minutes. However, there may still be one this winter! Moreover, having studied previous Jules Verne Trophy record attempts, skipper Yann Guichard has noted that the original cut-off date for setting sail by 15 January could easily be shifted… Indeed, among those who have managed to improve on the original time established by Bruno Peyron (79 days 06 hours and 16 minutes), who set off in early February 1993, Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston set the clock ticking on 16 January in 1994 (74 days 22 hours and 17 minutes), Olivier de Kersauson on 6 March in 1997 (71 days 14 hours and 22 minutes), Bruno Peyron again on 14 February in 2002 (64 days 08 hours and 37 minutes) then 25 January in 2005 (50 days 16 hours and 20 minutes) and Franck Cammas on 31 January in 2010 (48 days 07 hours and 45 minutes)…

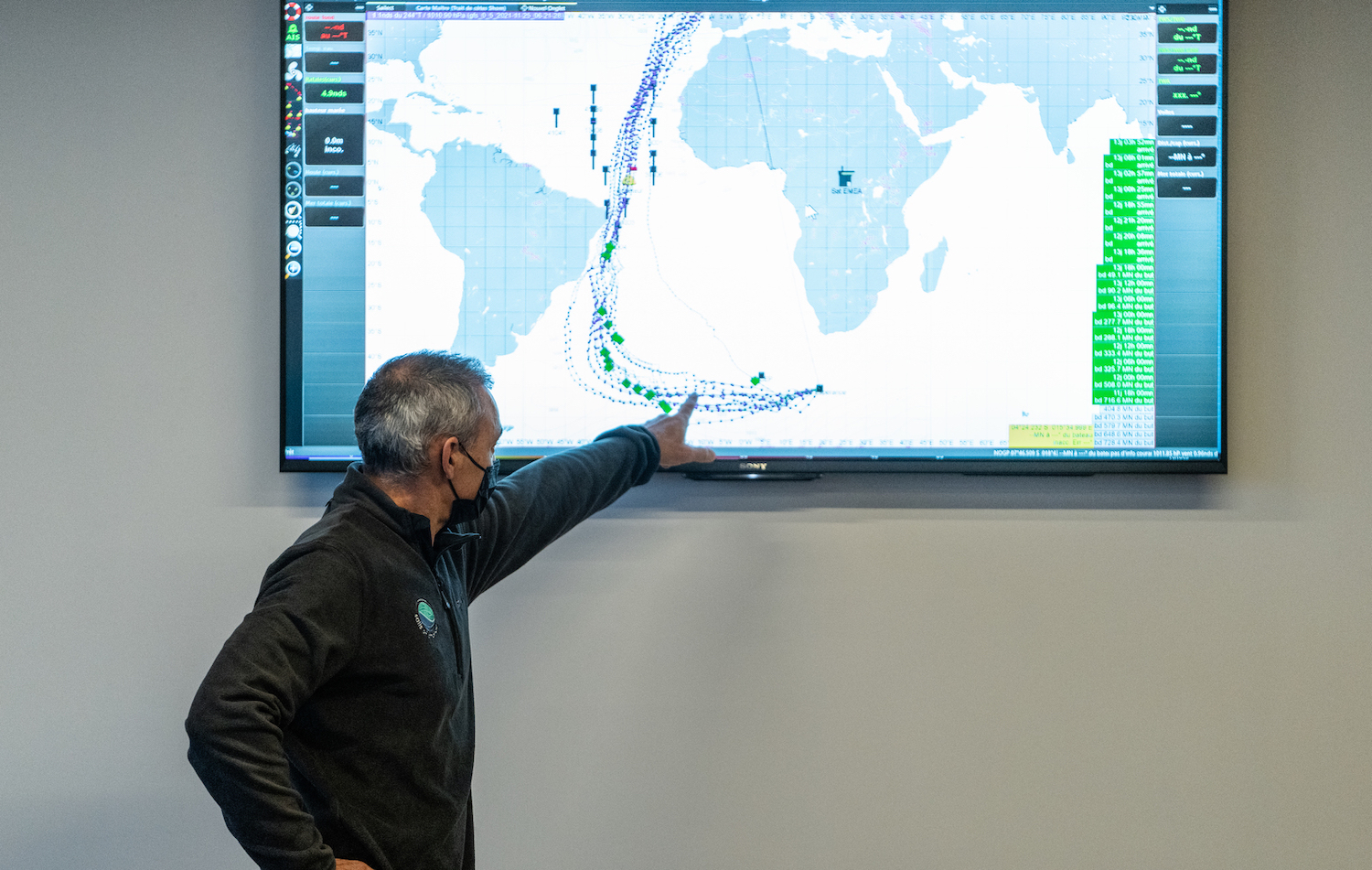

Of the eight improvements on the Jules Verne Trophy record in the past 27 years, five set off after New Year, or even in the run-up to Easter! This means there’s still a few additional days’ leeway, since the North Atlantic weather situation has not been positive so far. Sails of Change did come close to setting sail twice before the winter solstice, but in the end the situation would not have enabled them to reach the Cape of Good Hope in a fast enough time. Indeed, today’s record attempts must set their sights on the tip of South Africa as it’s no longer enough to cross the equator in a sub-five-day time (which the giant trimaran has already managed several times before). What’s key now is to post a time at the gateway to the Indian Ocean that is close to, if not improves on, that of the record holder!

“Originally, we planned to be on standby until January 15th, but the weather situation really hasn’t been favourable over recent weeks… As a result, we’ve decided to continue the standby until the end of January. There’s nothing unusual about that, as several attempts and indeed Jules Verne Trophy records have set sail after New Year or even after January! We knew that there are years with opportunities and years without. It’s hard to say whether climate change has an influence, but one thing for sure is that there are no established trade winds right now because the Azores High is not in its usual position. There is a string of low-pressure systems and sometimes these are even rolling around the latitude of the Canaries…” explains Yann Guichard.

Patience and time…

“Patience and the fullness of time do more than force and fury”, says the proverb penned by La Fontaine in ‘The Lion and the Rat’ fable. However, the Azores High has not been very cooperative of late, with a prolonged stretch of calm conditions offshore of the Cape Verde archipelago and the odd depression at the latitude of the Canaries! In these conditions, the much sought-after trade wind for a rapid descent to the equator has been sadly lacking… And what about its counterpart in the South Atlantic, Saint Helena? Well, it too has vanished into thin air, deserting the island which proved fatal to Napoleon, and lounging between Argentina and Gough Island, even splitting up into several cells at times, which twirl around the Falklands and the Crozet archipelago.

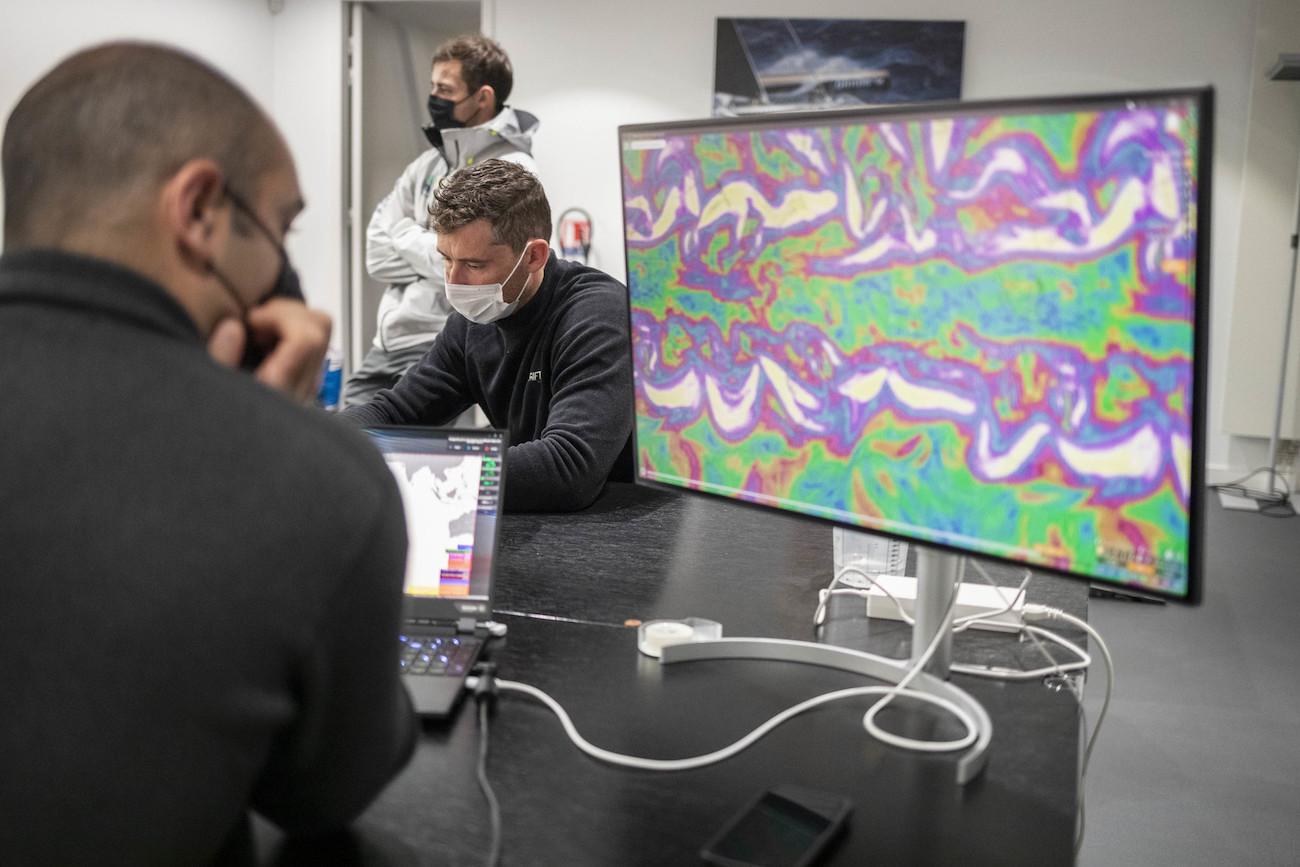

“The reliability of weather forecasts is now very good for up to ten days in advance. If the configuration is not favourable in the South Atlantic, there is little point in setting off and taking two weeks to reach South Africa! It’s important not to lose sight of our objective: to at least be inside the time set during the previous record, especially so at the Cape of Good Hope. Equally, offshore of Brazil, we also need to envisage hitching a ride across the Southern Ocean on the back of depression, until we’re at least halfway across the Indian Ocean…” concludes the skipper of Sails of Change.

In short, haste is not something that will colour the fourth attempt at the round the world record by Yann Guichard, Dona Bertarelli, and their crew. Even though the current weather pattern is unsurprising, with the additional challenges posed by the pandemic situation, it’s important to maintain a sense of proportion. The reference time for the Jules Verne Trophy is particularly low now. To stand a chance of improving on it, the crew will need to pass the longitude of the Cape of Good Hope in around a dozen days. Indeed, the current record for this section, set in 2017, equates to 12 days 21 hours and 41 minutes. It’s during this first section of the Jules Verne Trophy that the record could be won. It is one thing to claw back a few hours in the Southern Ocean, or even in the climb back up the Atlantic, but actually pulling it off is quite another…

2021 crew on Sails of change

Yann Guichard – Skipper

Dona Bertarelli – Onboard reporter

Benjamin Schwartz – Navigator

Jacques Guichard – Watch leader

Xavier Revil – Watch leader

Duncan Späth – Sailor

Grégory Gendron – Sailor

Julien Villion – Sailor

Thierry Chabagny – Sailor

Jackson Bouttell – Bowman

Yann Jauvin – Bowman

Replacements: François Morvan & Yann Éliès

Jean-Yves Bernot – Onshore router